Beautiful Gaza

We have gone from a war on an abstract noun (terror) to a war on immigrants and asylum seekers. The southern border has been declared a military zone and crossing any border has left tourists, students, green card holders, and citizens prey to arbitrary questioning and possible detention. Another Columbia student was kidnapped, and in Gaza the genocide continues unabated. No humanitarian aid has entered Gaza since March 2nd of this year, and this week Israeli defense minister Israel Katz announced that none will enter. His brazen remarks about the weaponization of food are basically the trumpeting of a war crime, but who will hold Israel to account?

Yesterday 25-year-old Fatma Hassona, a writer and photographer, was killed in Gaza. In January 2024, she was the sole survivor of an Israeli airstrike that killed most of her. On April 16, she and the remaining members of her family were killed in another airstrike in Gaza City. She was mourned in Gaza by young people who knew her or knew of her work.

Nadera wrote on Facebook, I could not sleep, Fatma, after you were killed. I saw all your photos as if they were glued to my eyelids, and I saw your words and texts that I read over and over in front of me in lines like a fence. Your departure killed me, Fatma, but it also killed our whole generation.

Sahar wrote to me, I’m thinking about Fatma, I think about her fiancé. She had only been engaged for two months, and she dreamed of a good life like any other girl in Gaza. I carry something like a rock on my heart and tonight it feels heavier than that. Fatma is gone. Mahasen, the painter, is gone. Dina, the painter is gone. Dhargham is gone (he was working on presenting small plays for children in tents). Muhammad Sami is gone. He was playing with children in the Baptist Hospital building when it was bombed last year. The friends I know are disappearing one by one. I swear to you that yesterday I felt that Gaza was extinguished, completely extinguished when Fatima left. You don’t know how much Fatima inspired girls like me and Nadera and all of us with her strength and her love for everything. By photographing the beautiful Gaza, which is still beautiful. What do we have left now?

I wrote back to Sahar:

I know that it is so hard because of the suffering of your people, of the destruction of Gaza, and because of the sense of powerlessness in the face of this unrelenting violence and cruelty. I am far from Gaza and in a basically safe place with plenty of food and water, but I struggle here to not give into despair because of this sense of impotence in the face of their depravity (all these horsemen of the apocalypse). I repeat this motto over and again, “The only recognizable feature of hope is action.” And I try to do something every day. Being in touch with you, helping you edit poems, sending your poems out to magazines…working on your graduate school applications, following up on them. These are things that give me hope. I want you to try to keep your eyes and your heart pinned on your bright future. Mourn your losses, suffer for your people, but don’t give up hope.

Repeat after me: The only recognizable feature of hope is action (Grace Paley). Choose your lane, find your people (Mariame Kaba). Freedom is a constant struggle (Angela Davis). The voice of the people is louder than the roar of the cannon (Armenian proverb).

Yours in struggle,

Nancy K

READ

My mentee Nadera Mushtha’s piece on the destruction of Gaza’s cemeteries: This genocide must be stopped, so that our city that was once a calm place for both the living and the dead will stop being a rubble-strewn necropolis.

Ben Ehrenreich’s beautifully written and wrenching piece about the West Bank in Harper’s: The camp’s young men had seen enough to believe that they would be killed whether they fought or not. “So, they started asking themselves, ‘Why wait for them to kill us?’

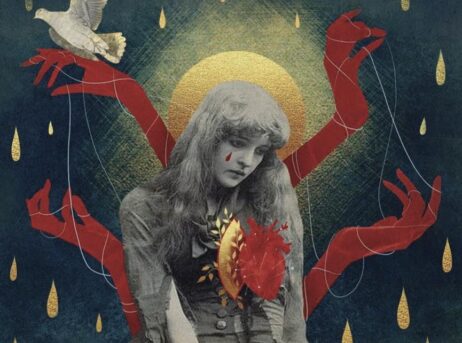

The following are all pieces related to the launch of my novel earlier this month. An essay I wrote for LitHub about my grandmother, a 1940 Shirley Temple movie, the Armenian Genocide, and my writing life. An interview I did with photojournalist and photo editor Aline Manoukian on the 50th Anniversary of the start of the Lebanese Civil War via Hyperallergic. Kate Tuttle wrote about the new novel for The Boston Globe (sorry it’s behind a paywall). An interview I did with Eleanor Bader for In These Times. Coverage of our The Politics and Poetics of Memory panel on April 1 at OxyArts. A snappy Q & A I did for the Armenian International Women’s Association (AIWA). Coverage of a visit I made to talk with 8th grade students at St. Gregory’s Armenian School in Pasadena.

WATCH & LISTEN

Also related to my book launch. Super dynamic Author2Author Podcast interview I did with Bill Kenower. Video recording of my conversation with Nanore Barsoumian as part of the Literary Lights series on April 15. A Twitter live interview about The Burning Heart of the World with NPR’s Scott Simon for his Open Book series.

SUPPORT

If you would like to support The Burning Heart of the World and you’re a member of Goodreads, you can review and rate the new book here. You can ask your local public library or your neighborhood independent bookstore to order it. Or you can purchase a copy directly from Red Hen Press via IndiePubs.

April 17, 2025