#bakingnotwriting

Soon after I signed the contract for my second novel, my agent at the time suggested that I start writing reviews. She explained, “First novels are easy. You get lots of reviews without much trying, but with a second novel, it’s much harder. The way to get reviews for your own book is to write them.” It sounded like a terrible idea—I would only want to write reviews for books that I loved. If the book were bad or even mediocre, I could only think of how much time would be wasted. And then I hated the idea of saying mean things in print about another writer’s work even if the book were abysmal. I had noticed in the New York Times Book Review that the editors seemed to assign titles in two ways—they either gave the book to someone who wrote similar work and would be likely to praise it, or to someone whose work was so dissimilar that they were likely to loathe it. I decided to ignore the advice, although I felt a pang when my second novel was published and it received only seven mainstream reviews (less than a quarter of what the first novel had garnered).

After declining to write reviews, about five years ago I decided that I would no longer write jacket blurbs for other writers. I thought that I either had to go the Gary Shteyngart route and offer praise to anyone who asked, or to quit writing blurbs altogether. I admired Shteyngart’s stamina and felt grateful to the people who offered advance praise for my novels—among them Chris Bohjalian, whose graciousness is legendary—but my Armenian Evangelical upbringing had made polite prevarication a painful exercise. Declining all was a way to avoid having to choose, which would hurt people’s feelings, or having to lie, endorsing something about which I felt little to no enthusiasm. Earlier this year when the editor of the American edition of Atef Abu Seif’s The Drone Eats with Me sent me an advanced reading copy (known in the business as an ARC) soliciting a quotation, I told her that while I wasn’t writing blurbs, I would read the book and if I liked it I would write a review. Happily, I loved it, and I wrote a review for In these Times.

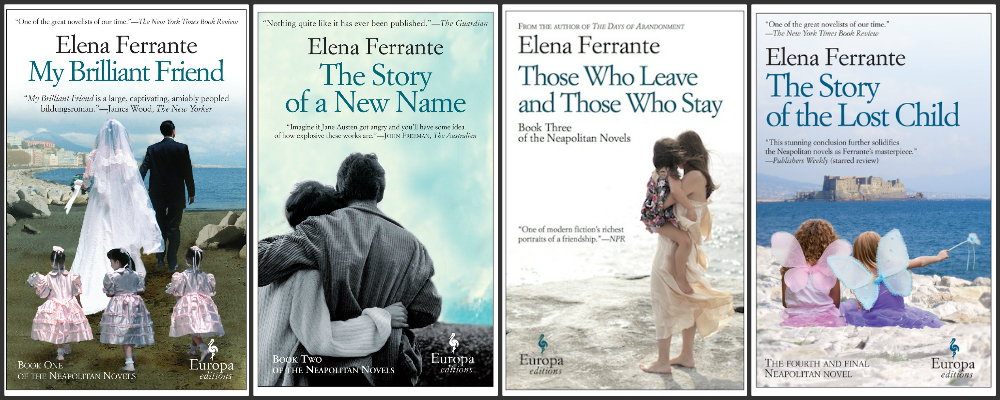

As a counter to my literary parsimony, I will say that when I love a book, I loudly share my enthusiasm with friends and on social media platforms. If I adore a book, I will buy a dozen copies and give them as birthday and holiday gifts. Some titles that I have distributed in this way include Vasily Grossman’s An Armenian Sketchbook, Suad Amiry’s Sharon and My Mother-in-Law, and Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend. My current passion is Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women, a dazzlingly smart series of prose poems about writing, work, love, parenting, sewing, shopping, literature, philosophy, late capitalism, and not writing. Boyer’s book, full of wry observations, artfully muted fury, as well as surprising humor and tenderness, reminds me of the work of poet Anne Carson and micro-story writer Lydia Davis, except with an explicit class analysis.

Boyer describes a shopping outing with her young daughter, where their meager budget results in sadness and weeping when mother tells the daughter they cannot afford the desired pair of shoes. When the mother is on the verge of tears herself, the daughter admonishes her, “ ‘I am still a child and am learning to control my impulses and emotions. you have had many years of dreams and realities to learn from so there is no excuse for you to cry.’” In “A Woman Shopping,” Boyer outlines a book she would like to write with the same title as the poem. It ends, “But who would publish this book and who, also, would shop for it? And how could it be literature if it is not coyly against literature, but sincerely against it, as it is also against ourselves?”

In an interview posted on the Poetry Foundation site, Boyer explains,

This is probably totally obvious to anyone who has read the book, but I’ll still say it: by “garments,” I mean “literature.” And literature is against us. And when I say “literature,” I mean something with historical specificity, seen with all of its brutality intact, with our own intact too, not as we might define it from its exceptions, despite how these exceptions are honorable and instructive and how much we might ground our work in them.

And this is going to get kind of long, so I apologize for that, but by “us” I actually mean a lot of people: against all but the wealthiest women and girls, all but the wealthiest queer people, against the poor, against the people who have to sell the hours of their lives to survive, against the ugly or infirm, against the colonized and the enslaved, against mothers and other people who do unpaid reproductive labor, against almost everyone who isn’t white—everyone who has been taken from, everyone who makes and maintains the world that the few then claim it is their right to own. And by “against,” many of us know this “literature” contains violent sentiments toward us, is full of painful exclusions, but that isn’t even the core of its opposition to us. How “literature” is also against us is that it is a magic circle drawn around the language games of a class of people—the rich and powerful and those who serve or have served them. It gives (or appears to give, like any mystification) these words a permission and a weight, dangles the ugliness in our faces and names it beauty, gleefully shows off stupidity and claims it as what is wise.

Part of what I admire and identify with here is Boyer’s refusal to bow down to literary gatekeepers while stubbornly continuing to write. In the pieces “Not Writing” and “What is ‘Not Writing,” Boyer describes the forces making writing difficult, if not impossible, for her as a working class woman, a single mother, and an outsider to high “culture.” But the production of these poems defies these obstacles—from illness to envy. She says, “There is envy which is also mixed with repulsion at those who do not have a long list of not writing to do.”

In closing, here is one of my favorite passages in Garments Against Women from “The Innocent Question.”

On the local radio show a man who won a Pulitzer prize in fiction explained that one must write every day because if a person does not write everyday a person forgets how to access the subconscious. If one did not write everyday then whenever a person comes back to writing she would have to learn to write from the beginning again. This has always been my plan. I would like to not know how to write, also to know no words. I believe this prize winning novelist believed that the mind had two places, the conscious and subconscious, and that literature could only come out of the subconscious mind, but that language preferred to live in the conscious one. This is wrong. Language prefers to live on the internet.

Nancy Kricorian