Audio book, radio interviews and other news from the tour

I know it sounds a little corny, but I am thrilled that Suzanne Toren has recorded the audio book for ALL THE LIGHT THERE WAS. Suzanne and I spent several hours on the phone going over the Armenian names and phrases in all three of my novels—audio versions of ZABELLE and DREAMS OF BREAD AND FIRE will be available soon—and I was awed by her ability to repeat things back with perfect pronunciation.

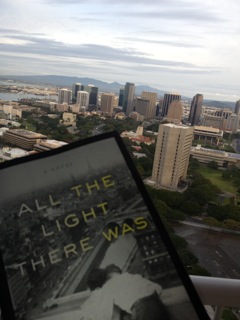

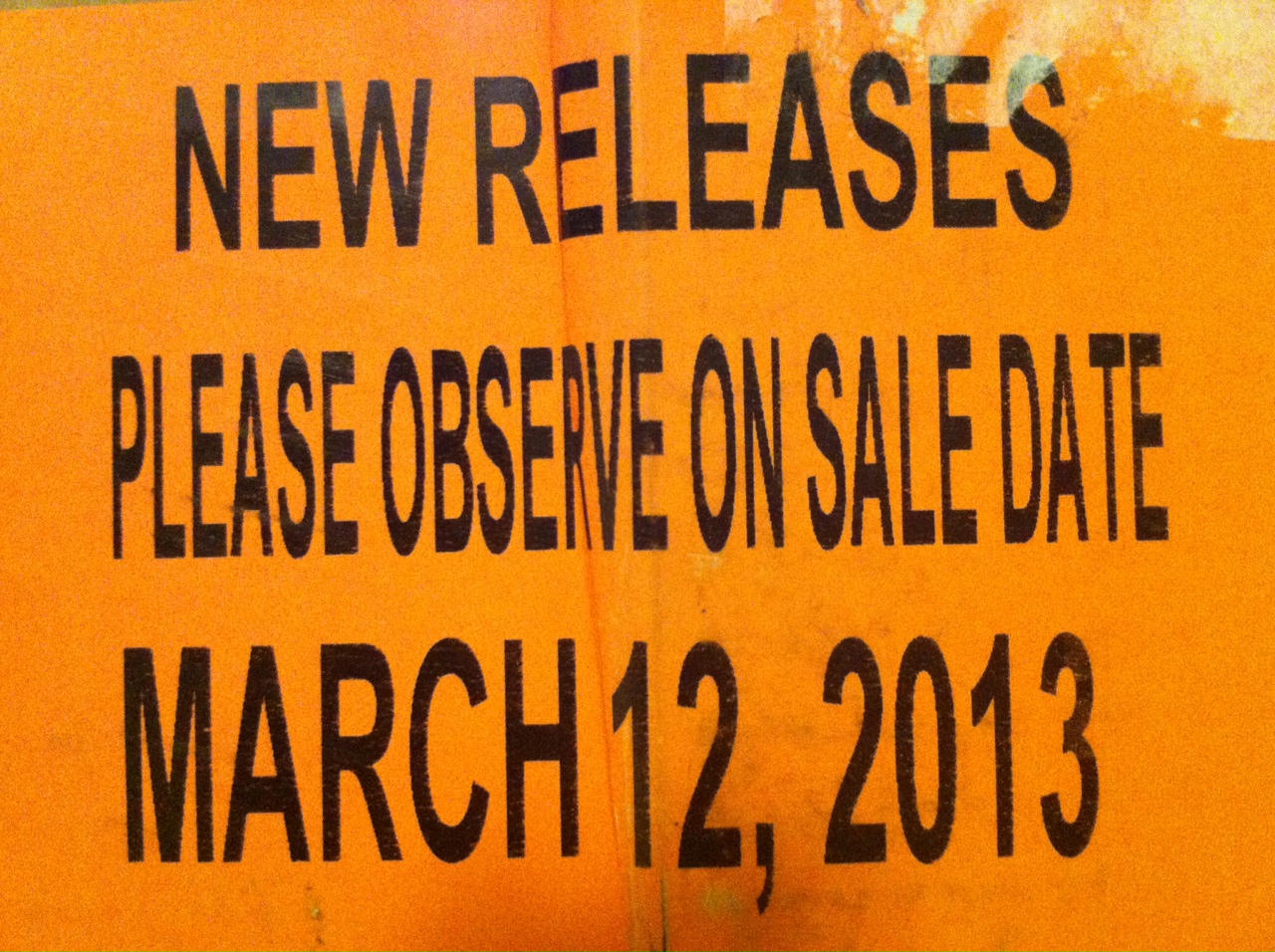

ZABELLE and ALL THE LIGHT THERE WAS are downloadable as ebooks, and I recently signed a rider to my Grove/Atlantic contract for DREAMS so that ebook will soon be online as well. I feel grateful that all three of my novels will be available in all three formats—a book to hold in your hand, an electronic version to read on your device, and an audio version for your listening pleasure.

This week I did two radio interviews, one with the inimitable Leonard Lopate on WNYC and the other with the Armenian Radio Hour of New Jersey. More radio and even TV interviews are on the horizon. I will share when they are available.

I’m posting a favorite photo from the California leg of the ALL THE LIGHT THERE WAS tour. I’m standing with some members of the Armenian International Women’s Association San Francisco Chapter at Book Passage in the Ferry Building. Their outpouring of warmth and enthusiasm made the evening one of the highlights of the trip.

March 29, 2013