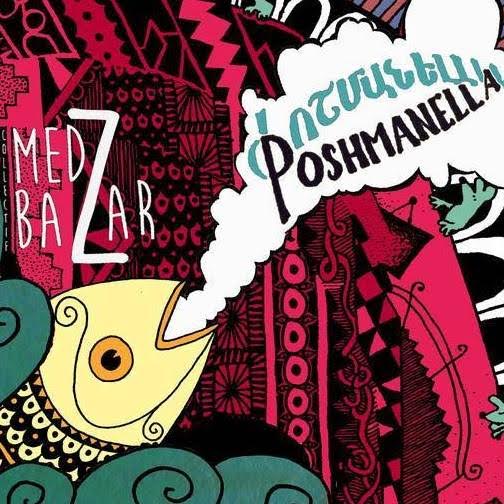

Open Letter from Medz Bazar

My friends from the Paris-based musical band Collectif Medz Bazar asked me to help disseminate this open letter. It tells a sad story about intolerance, but the text of the letter itself is a beautiful expression of the band’s commitment to amplifying the humane in the human through music.

An open letter to those who made sure the musical band Collectif Medz Bazar would not be able to sing its repertoire during the “Nuit arménienne” (Armenian night) of Arnouville on April 22nd 2017, because of their hostility towards the songs in the Turkish language.

Until recently, we, the Collectif Medz Bazar, were happy to count among the participants in the “Nuit arménienne” (Armenian night), an event organized by the municipality of

Arnouville, France, in partnership with several Armenian associations, this coming April 22nd. The event organizers informed us that a few individuals and Armenian associations of

Arnouville were adamantly against our playing the songs of our repertory that are in Turkish and that they were doing everything in their power to stop us from singing them. Since we did not receive any message directly from them, we cannot speculate about their reasons.

Because of this, and to avoid any misunderstanding, we sent them a letter last month via the event organizers, very clearly identifying our approach and explaining that nothing in our project goes against the spirit and feeling of the event.

Having read our letter as well, the event organizers were inclined to pursue our participation, because not only did they feel that our repertory didn’t pose any problems, they expressed their adherence to the values that we defend. But the response of the individuals and associations in question was total rejection, once again without bothering to address us directly. What’s more, they intensified their campaign against our repertory, forcing the municipality to disinvite us, the latter being afraid that on this date (April 22nd), which is close to both the annual commemoration of the Armenian genocide and the 1st round of the presidential elections in France, some sort of disturbance might occur during the event.

We are aghast and totally speechless at the relentlessness with which these individuals and associations worked to sabotage a concert that had been scheduled a long time in advance, attacking a symbol, in this case a language, as if it were an enemy. We consequently invite these persons and associations via this open letter, reformulating our initial letter, to assume their actions publicly or, if they do not dare to do so, to have the decency to reconsider their actions and to renounce such practices in the future.

The Collectif Medz Bazar, a musical ensemble based in Paris, is composed of musicians of various origins: Armenian, Turk, Franco-American. The group got together not with the intention of symbolizing reconciliation between Armenians and Turks, but simply to share with one another their artistic creativity and friendship. But the Armenian-Turk factor does play a part in that a reciprocal curiosity did exist, a need to know, to be able to laugh, cry, speak openly, sing and play music together – this desire surely drew us towards one another. During a performance, our only propos is the music we present to the public, which is drawn from our respective cultures in the intimacy and spontaneity of each person; our mother tongues are thus the very basis of our repertory and their presence is indisputable.

It would appear that for some Armenians, singing in the Turkish language is an issue.

The few anonymous Arnouville individuals are not the first to protest, and it’s easy to imagine a sizeable group of Turks who think exactly the same thing about singing in Armenian. Their respective reasons or justifications being, without any doubt, completely different. But in both cases, the result is the same: they both censure a language, incite xenophobia. But observe this obvious fact: one can say anything one wants in any language. A book denying the Armenian genocide can be written in Armenian just as a book presenting a thorough investigation of this subject can be written in Turkish. A language, a culture cannot be held responsible, even symbolically, for the crimes perpetrated by those who claim said language or culture as their own. A language is not “owned”: some Armenians speak Turkish, some Assyrians speak Kurdish; this letter is written in French and translated into English. The Collectif Medz Bazar does not represent any national culture, we draw from all living cultures. The culture of Turkey, like that of many many other nations, is multiple and as varied as the people who live there. When we sing in Armenian, in Turkish, in French, we are not glorifying the Armenian, Turkish or French cultures. Reducing a language or a piece of music to a national symbol is not the work of an artist. But offering a part of yourself by singing in your mother tongue, a simple, generous act, is. Why, then, attack persons whose only intention is to share their music and the joy of being able to sing together?

Our project forms part of a global change, fragile but real, in relations between

Armenians and Turks. Initiatives such as ours are not isolated cases, there is today a community of persons sharing the same aspiration: to communicate, get to know each other better, try to live together, make progress on an individual basis given the lack of any political impetus. This aspiration and mutual coming closer of two traditionally hostile peoples, although it cannot replace the necessity of a political resolution to the Armenian Question, does serve to raise awareness at an individual level and will undoubtedly contribute to collective healing, however slow it may be. At present, Armenians can openly commemorate with the Turks, with the Kurds: a slow awakening of awareness has been in progress for several years now. To turn one’s back on this progress means returning to the status quo and would be equivalent to turning one’s back on those who, sometimes putting their lives at risk, assume a position that goes against the current dominating ideology. In the name of what combat?

Music is a universal language that can transmit far more that words can. The next time your prejudices make you rise up against our music (or against anyone else), take a minute to listen to the rhythms and melodies, the thoughts and emotions that we express. You will understand the sincerity of our work.

With this open letter, we join our voices to all those who defend the fundamental values of freedom of expression and brother/sisterhood among peoples.

We invite you to do the same.

The Collectif Medz Bazar

April 2017

Nancy Kricorian

April 21, 2017