Shoulder to the Wheel

The horsemen of the apocalypse continue their rampage against immigrants, trans people, women, abortion, history, the environment, and dissent. Their motto seems to be: A fire on every corner, a fox in every henhouse, a grifter and thief with a hand in every till. Meanwhile, and relatedly, the Israeli government launched a war against Iran that the U.S. government joined, and while that seems to be over for the moment, these vile collaborators continue apace with a genocide in Gaza. All of this is demoralizing, but we must keep our proverbial shoulders to the wheel, and we need to do it together.

On a brighter note, Columbia graduate and former student protest leader Mahmoud Khalil was released from detention and returned to his wife and infant son in New York City. I was at the rally held on the steps of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine on Sunday afternoon where Mahmoud spoke passionately about his personal ordeal and the suffering of the other men he met in the ICE detention facility in Louisiana. He said his imprisonment had only firmed his resolve to keep speaking out for Palestine. He then led a march to the gates of Columbia University to denounce the administration’s hypocrisy. His attorneys are still fighting the government’s attempts to have him deported because they claim that his speech is a “national security threat,” but at least now, he is home with his family.

Today is the mayoral primary election in New York City, where Zohran Mamdani is running neck-and-neck with bully and sexual harasser Andrew Cuomo. Because the city now uses ranked choice voting, the results will likely not be known until July 1st. On a side note, I have known Zohran since he was 8 years old and an elementary school classmate of our oldest child. And no matter what the result, I have felt like a proud auntie watching his excellent and practically flawless campaign.

My friend Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian’s inspiring book FOREST EUPHORIA, which was published on May 27, is already a national bestseller, and you can read an excerpt of it on LitHub. Patty and I will be in conversation about the book on Saturday, 28 June at 1 p.m. on Zoom as part of the International Armenian Literary Alliance’s Literary Light Series. You may register to join us here.

The Massachusetts Review published two poems by friend and mentee Sahar Rabah, who is still in Gaza where starvation and daily bombardment continue and are barely covered in U.S. mainstream media. The MassReview also published my young friend T.S.’s powerful piece Why Must We Be Heroes? My mentee Nadera Mushtha’s piece about higher education in Gaza during a genocide was published by The Guardian.

Leila Sansour wrote a clear-eyed if devastating analysis of why Israel is using starvation as a weapon of war against the entrapped and besieged Palestinians in Gaza. In the face of this depraved cruelty, her conclusion is that we must support the rebuilding of Palestinian society: “The strategy to confront it should therefore focus on unwavering commitment to rebuilding kinship, a sense of shared purpose, restoration of community, and civic dignity.”

Let’s follow the example of Ms. Rachel for Littles and do something every day that shows our commitment to creating a world where all children are cherished, where no children are bombed and starved, where families are not torn apart by masked thugs, and where all beings, human and non-human, are respected.

Yours,

Nancy K

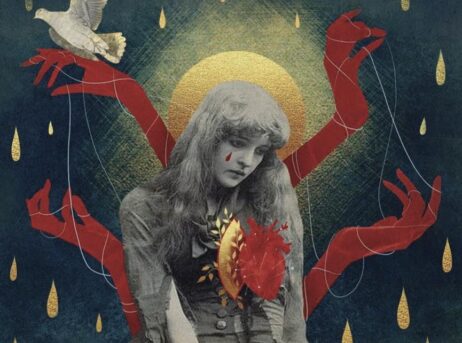

P.S. I will be joining The Markaz Review Book Club’s meeting to discuss THE BURNING HEART OF THE WORLD on Zoom on Sunday, July 27 at 1 p.m. ET/19 CET. You can learn more about the book club and sign up for the event here.

June 24, 2025