Respect Your Process

When I was in college, I studied for one semester with a poet who dispensed counsel the way my grandmother handed out hard candies. This poet told me that if my boyfriend didn’t make me feel like I was the most beautiful woman in the world, he wasn’t doing his job and I should fire him. Another memorable bit of advice was about writing, and left her lisping voice echoing in my head with this mantra, “Respect your process.”

During my student days, I was prolific. I wrote a poem a day in long hand on narrow ruled yellow notepads, and often they sprang fully formed from my head like Athena. I rarely revised, and often didn’t even type them. I would bring them to my professor on the yellow notepads, he would make a few comments, and say, “Just keep writing.” And so I wrote and wrote and wrote. In graduate school I learned about revision, and often took a poem through ten or more drafts before I was satisfied with it and moved on to the next one. This was in the old days when it was possible to keep track of drafts because I typed each one on a sheet of paper using an IBM Selectric Typewriter.

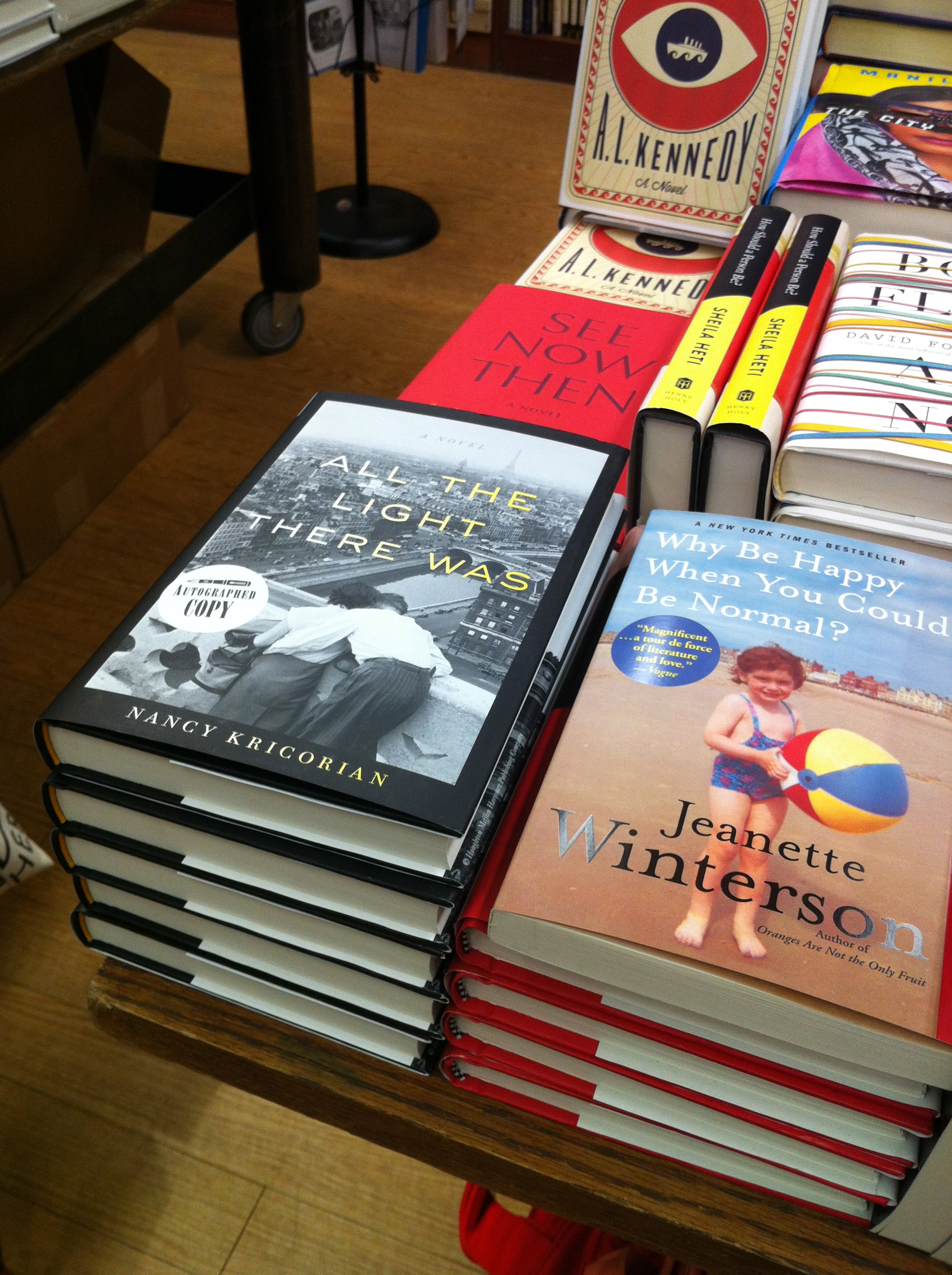

By the time I started working on my first novel, Zabelle, I was writing on a computer. Gone were the yellow lined note pads for the first draft, and gone also was the stuttering and humming electric typewriter. The only way I could think of attempting something so long and unwieldy as a novel was by breaking the task into story chapters. I had the stamina to write one ten-page chapter, and after that was done, I started the next. Once I had a stack of these chapters, I figured out how they fit together and then rewrote them so they made a coherent, if episodic, narrative. Revising a text that was two hundred and seventy pages long was a much more daunting prospect than rewriting a one- or two-page poem. By the time I got through the last chapter, I went back to the beginning and noticed more things that needed fixing, and went over the whole thing once again. Working on a computer, there was a lot of continuous fiddling with bits here and there, so it was harder to keep track of how many drafts I did, but it was probably upwards of three before I even sent it to my agent. With her suggestions, I did another draft before she showed it to the editor. There was another pass with the editor’s notes before the production process started. The copy editor did a thorough once over, and then it was done. This was pretty much how it went with my two subsequent novels, Dreams of Bread and Fire and All the Light There Was.

You would think that the fourth time I approached this kind of project, I’d march ahead with assurance. But no, when I started writing my latest novel, I felt as though I were at the bottom of an enormous mountain peering up at a peak that was enshrouded in clouds. How would I ever manage to get to the top? I’m a slow writer—in part because I do a massive amount of research before I start writing, and because other aspects of my life (my family’s needs and challenges, my geriatric dogs, my work as an organizer, as well as the distractions of our calamitous political moment) often crowd out my writing. I can’t write for more than two hours a day. I used to be able to produce two pages in two hours, but now I eke out one page a day.

At one point over a year ago, I said to my spouse in despair, “How am I ever going to get this thing done?” He answered, “If you write one page a day, you’ll eventually finish it.” In other words, “Respect your process.” And much to my surprise, at the end of October I printed out a completed rough draft of this novel about an Armenian family in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. It opens with this same family in New York on 9/11, and ends with a folk tale about a girl who talks with birds. It’s rough, and it needs a lot of work. But it’s done, and my first and most trusted reader, the aforementioned spouse, confirmed that the structure is sound—this was my biggest worry.

I took a hiatus from the novel so that I could come back to it with fresh eyes. While on this break, I wrote a talk that I delivered on a panel at Columbia on November 20, which was published last week by the Armenian Weekly. Also in November, Egg & Spoon Theatre Collective staged an off-off-Broadway adaptation of Zabelle. My novel All the Light There Was recently appeared in Turkish translation from Aras in Istanbul, which had previously published Dreams of Bread and Fire. And three weeks ago I saw the cover of the Arabic translation of Zabelle, which will be published in February 2020 by Fawasel Books in Syria.

And now it’s time to get back to work.

Nancy Kricorian

December 10, 2019