On the Occasion of The Saturday Mother’s 500th Vigil for the Disappeared

Today in Istanbul The Saturday Mothers held their 500th vigil for the disappeared. When I was in Istanbul in September at an international feminist workshop on mass trauma, memorialization and activism for change, the conference participants joined The Saturday Mothers/People at their 495th weekly vigil. Most of the photos held during the demonstration were of Kurdish men who had been disappeared by the Turkish government in the 90’s. But among the sea of faces, I also saw several photos of Armenian intellectuals, such as Krikor Torosyan, who were arrested and murdered on April 24, 1915. The man who held that photograph was clearly not related to Torosyan, but here again the simple act of making visible a single, near-forgotten image transformed that space of protest into something hopeful and transcendent. The Occupy Wall Street slogan “all of our grievances are connected” was made manifest in this display of solidarity, and brought to mind the expansive humanity of the Soviet Russian writer Vasily Grossman.

Grossman, who lived from 1905-1964, was a Soviet Russian writer and journalist. He was also a Jew whose mother was murdered by the Nazis at Berdichev. At the close of World War II, he was one of the first journalists to see and write about the Nazi death camps in a searing piece entitled “The Hell of Treblinka.” His masterpiece, the World War II novel LIFE AND FATE, was never published during his lifetime because of the complex honesty of his portrayal of life under Stalin. The KGB confiscated the typescript in 1961, and the novel was not published in Russia until the late 1980’s.

In 1962, after the arrest of his novel, Grossman was offered a probably compensatory job translating a long Armenian war novel. He went to Armenia, where he wrote a memoir about his stay that is a humane and insightful meditation on Armenia and Armenians, and offers as well a subtle, understated analysis of power relations during Soviet times. In the final chapter there is a poignant description of how, at a time when anti-Semitism was rampant in the Soviet Union, during the toasts at an Armenian village wedding, local people spoke with compassion about what had happened to the Jews during the Nazi occupation. Grossman wrote,

Never in my life have I bowed to the ground; I have never prostrated myself before anyone. Now, however, I bow to the ground before the Armenian peasants who, during the merriment of a village wedding, spoke publicly about the agony of the Jewish nation under Hitler, about the death camps where Nazis murdered Jewish women and children.

We still live in a time when people’s tribal loyalties often dictate political alliances, but this gesture of solidarity described by Grossman is to me a model of how we need to reach outside our own narrow interests to take up the struggles of people beyond our immediate community. As an Armenian-American I can say it is a great thing to lobby for Armenian Genocide recognition and to advocate for the Armenian cause, but for a progressive this is insufficient. I wouldn’t hope to dictate to anyone what issues to take up or what coalitions to join. There are so many: to name only a few examples, we have the Climate Crisis, scarily militarized policing in our cities, a “war on drugs” that is in actuality a war on people of color, a lawless drone assassination program being overseen by our current president, and human rights abuses from Kurdistan to Palestine. As Grace Paley so eloquently put it, the only recognizable feature of hope is action. The time to act is always now.

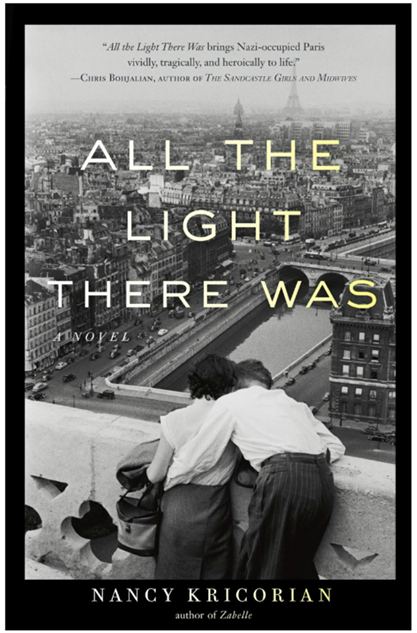

Nancy Kricorian

October 25, 2014