Day to Day

“Too much of a past, too little ahead, but wait a minute, we always lived day to day, so where’s the difference?”

~ Etel Adnan, Shifting the Silence (2020)

*

Last week my friend Barbara Harris passed away after a long illness, and Gerry, her beloved husband of 67 years, asked me to speak about her activism at the funeral this Monday. Barbara and I met in 2003 through CODEPINK NYC and worked closely together for over 13 years. In 2008, The New York Times ran a profile of Barbara and the campaign she organized working to keep predatory military recruiters from targeting vulnerable high school students. Mel, a former CODEPINK NYC staff member commented, “Barbara was a gift to the anti-war movement and the activist community. Whenever she showed up to a demo, I felt like things were going to be okay. She had so much knowledge and such a calming presence. Cristina and I joked about making Barbara dolls to carry around for reassurance when things got rough.”

And speaking of things getting rough, yesterday Azerbaijan launched a full scale military assault against the people of Artsakh, announcing the planned “evacuation” of the Armenian population. Of course, anyone who was following the news could have seen this coming, but that doesn’t make it any less devastating. The use of the word “evacuation” clearly indicates a campaign of ethnic cleansing. Governments, NGO’s, and human rights groups have issued condemnations, but the shelling and terror continued undeterred. The Azerbaijani Army is known for its torture and beheading of captured Armenian soliders, and even civilians are fair game for their violence and cruelty. The fourth century Amaras Monastery, established by St. Gregory the Illuminator, is now under Azerbaijani control. And if the Azerbaijani government stays true to form, they will say that it’s an “Albanian Christian” monument and sandblast the Armenian inscriptions. It’s heartbreaking and infuriating to watch all this happening in real time on social media while the world does nothing. And Turkey’s ever helpful Erdogan announced at the U.N. General Assembly yesterday that Armenia must open the so-called “Zanzegur Corridor” allowing Azerbaijani passage through the territory of the sovereign Armenian Republic. This morning a “ceasefire” was announced and the Azerbaijani army took full control of the area. I’m dreading what comes next. You can follow what is going on via live updates from EVN Report and you can contact your elected officials using this tool from the Armenian Assembly of America.

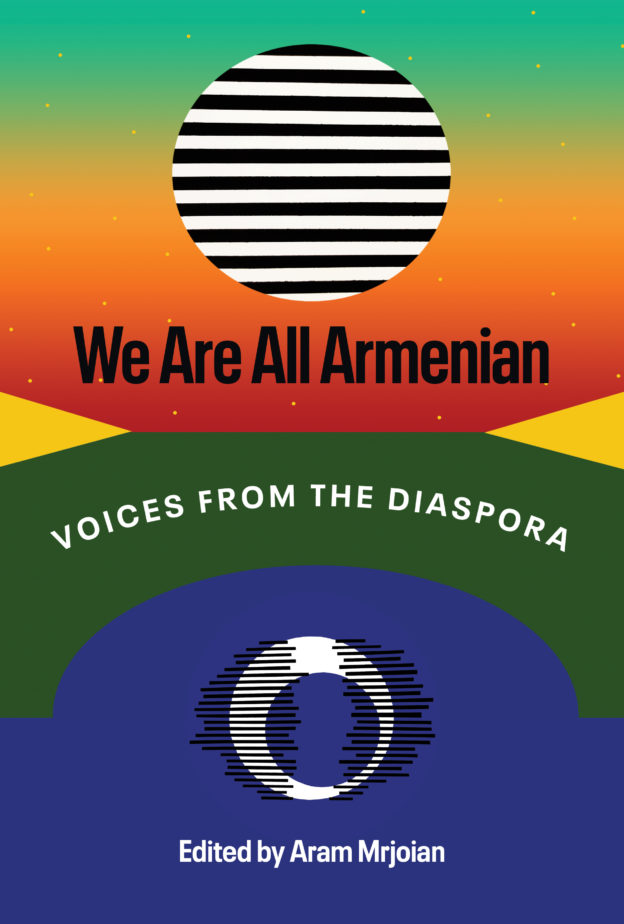

Yesterday I also received word from my literary agent that she was closing on the last few open points in the contract for my new novel with Red Hen Press, a small, independent, non-profit publisher based in Pasadena. Red Hen will publish The Burning Heart of the World, a novel about an Armenian family in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War, in 2025. This submission process was long and grueling, and I cannot tell you what a relief it is that the book has found a home, and with a press whose values align with so many of mine.

I’m leaving on Friday for a two-week trip called “The Mushrooms and Culture of Greece.” My friend Betsy and I will be traveling to Zagori in northwestern Greece with a group tour led by several radical mycologists. If you follow me on social media, expect to see lots of photos of mushrooms, food-laden tables, mountain villages, and the rocky shore.

Day to day, I try to open my heart to the sweetness of this tough world.

P.S. For your reading pleasure, here’s an interview with our filmmaker progeny. And here’s an article about The Wisdom of Fungi.

Nancy Kricorian

September 20, 2023