Extended Family: When Fictional Characters Show Up In Your Living Room

We hear that for many writers, the characters they create “come alive” during the writing process. But in what ways is that phrase more than a simple metaphor? And how is a writer supposed to manage the expanded household as it begins to fill up with progeny spilling over from the pages of a work in progress?

My third novel, All the Light There Was, which is set in the Armenian community of Paris during the Nazi Occupation, took ten years to research and write. In part I needed a decade because I had a great deal of research to do, but it was primarily due to the fact that I was juggling a few other jobs-running a household, raising two daughters (and it turns out that dealing with kids between the ages of eight to eighteen takes more space in your head than was necessary from zero to eight) and working for a women’s peace group trying to stop multiple U.S.-funded wars and occupations.

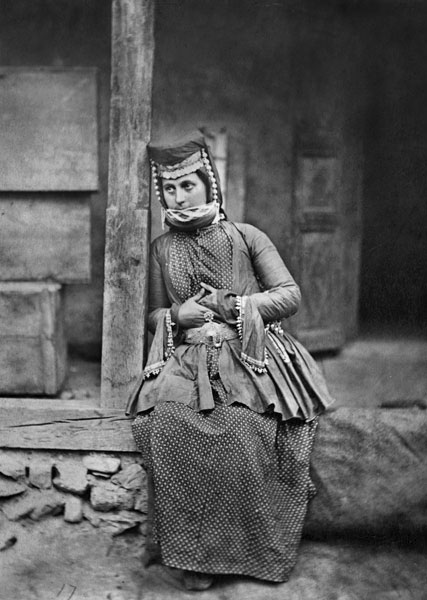

In order to recreate the atmosphere of the working class neighborhood of Belleville during the period the French refer to as Les Années Noires (The Dark Years), I read voluminously from histories, journals, collections of letters, and novels penned during and immediately after the war years. I went to Paris to tour the lycée that my narrator and protagonist Maral Pegorian had attended, and to interview octogenarian and nonagenarian Parisian Armenians who had lived through the war.

Through the research, several salient material details were impressed upon me again and again: during the Occupation ordinary people were hungry most of the time, during the four winters under Nazi rule Paris apartments were generally without heat, and Parisians were often in the dark both literally and metaphorically. Germany used France as its wartime breadbasket, making off with the lion’s share of French butter, milk, wheat, vegetables, fruit and meat. Food was rationed and even with ration tickets in hand shoppers were often unable to procure their due. Rutabagas and turnips, which had been used before the war as cattle fodder, were now a staple of French cuisine. The Germans also requisitioned French coal and other fuel, leaving Paris apartments unheated in winter. Nighttime blackouts meant the streets were dark and curfews often kept people in their homes after nightfall.

Once the bulk of the research was done, I disciplined myself to write two hours a day, five days a week, aiming for two pages a day. This schedule was mostly successful, except when one of the kids stayed home sick from school, or there was an emergency street demonstration.

While I was writing, I traveled back in time and across the ocean to Occupied Paris. I could not only hear the voices of my characters, but I could also feel the cold air seeping in the cracks around the window frames, and smell the dreaded rutabagas cooking in the kitchen. I fretted with Maral over her lack of bath soap, and shared the frustration of her cobbler father about his inability to get leather. But it wasn’t until the day that my husband asked me why we had seven jars of mustard in the pantry that I realized how deep this shared experience had gone.

It was true—there were seven jars of mustard in the pantry, and six jars of jam, along with more canned goods than we could eat in a winter. Without being conscious of what I was doing, I had stockpiled the foodstuffs that Maral’s family lacked in Paris in 1942. I had always thought of myself as spending hours living in the Pegorians’ world; what I hadn’t realized was that the characters had moved into my apartment. They were haunting our pantry, showing up in conversation through the Armenian proverbs I cadged from Maral’s father, and occupying my thoughts when I was supposed to be helping with the science fair poster. Once I became conscious of their presence as part of the family, I was better able to balance their demands with those of my real world children.

Ten years on, once the novel was completed, the manuscript handed over to my editor and the rest of the publishing team, the characters started to recede, and I missed them. But I’m glad too that they are soon heading out into the world and into the homes of my readers.

Now I’ve begun work on my next novel. It’s about an Armenian family in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. I’m excited, but a little anxious, about what life will be like with them in the house.

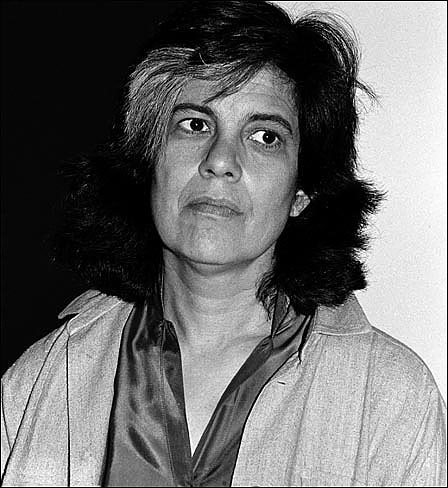

Nancy Kricorian

January 18, 2013