When I was in third grade our new teacher was different from any teacher we had ever seen at the Hosmer Elementary School in Watertown. Mrs. DeVoe was young and beautiful, with shoulder-length blond hair that flipped up at its ends. She wore mini-dresses with leather boots, and some days after school her handsome husband picked her up in a red sports car with a convertible top.

Each morning we started the day standing in a circle, holding hands and reciting proverbs. Things such as, “A stitch in time saves nine,” “When the cat’s away the mice will play,” and “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

I loved this activity and tried to find unusual sayings to share. I was particularly proud to offer this one: “What’s good for the goose is good for the gander.” Most of the other children didn’t know what a gander was.

We never discussed what a proverb was or why this might be a good way to start each morning. We rarely talked about their meanings. But the ritual provided a connection to communal wisdom. There was also something solemn and vaguely religious in it, although God was never mentioned.

A few years later I made a list of synonyms for proverb: adage, aphorism, axiom, dictum, maxim, and saw. Saw was the best one because it was a simple word with an esoteric meaning. There was another synonym—platitude—hinting at the fact that while proverbs might convey moral lessons and general truths, they could also be truisms that should be questioned.

At home we had other sayings. My mother’s favorites were, “If you don’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything at all,” “If you want something done well, you have to do it yourself,” and “There’s no such thing as an ugly baby.” My grandmother instructed, “Shut the light. Edison is richer than me” so frequently that it became a family mantra. My father was known to say, “That’s about as funny as a submarine with screen doors.” And he frequently quoted my Armenian grandfather’s motto: “I’m not a miser, I’m an economizer.”

This last was said in English, but it follows a pattern and rhyming structure that is common to Armenian proverbs as I later learned from studying them. Over a decade ago, I purchased a copy of Dora Sakayan’s Armenian Proverbs: A Paremiological Study with an Anthology of 2,500 Armenian Folk Sayings Selected and Translated into English, and it has been a source of endless interest and delight. I have since then sought out other sources—a 1932 bilingual anthology by an Armenian priest in Venice, short sections in books about Armenian folk tales and village lore, and of late many online compilations. My rudimentary Armenian language skills are good enough that I can read the original and compare different English translations. With the help of a dictionary I can even do my own.

I used Armenian proverbs as chapter headings in my second novel. I made lists of proverbs to deploy as I was creating a character in my third novel—Garabed Pegorian, a Genocide survivor, cobbler and father who makes sardonic comments about the Nazi Occupation his family suffers through in Paris. I’ve taken to posting Armenian proverbs on my Facebook author page and to Twitter, where they generate much response.

Here are some of my favorites:

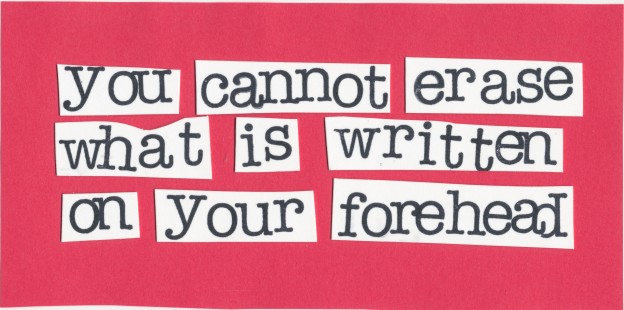

You cannot erase what is written on your forehead.

The hungry dream of bread, the thirsty of water.

A lost rope is always long.

Be neither sweet and swallowed, nor sour and spurned.

Toss your good deeds into the sea and the waves will carry them back to you.

The fool’s tongue is always long.

Literacy is a golden bracelet.

The lid rolled and found its pot.

From heart to heart there is a path.

A mother-in-law should be blind in one eye and deaf in one ear.

Walk with the devil, but don’t let go of his tail.

In a foreign place, the exile has no face.

Land of Armenians, land of orphans.

Land of Armenians, land of sorrow.

Heaven and hell are in this world.

If they send two baskets of shit to our city, one will come to our house.

It’s better to carry stones with a wise man than to eat pilaf with a fool.

It’s better to go into captivity with the whole village than to go to a wedding alone.

The person who looks for a friend without faults will remain friendless.

Grief for the loss of a child is a burning shirt.

Let’s sit crooked and talk straight.

Let it be one and fine.

What does the donkey know of the almond?

If you buy a donkey for the price of a cucumber, one day you will find it drowned.

I have a few ideas about what this last one means, but I’ll leave that to the reader’s interpretation.

Nancy Kricorian

December 21, 2012