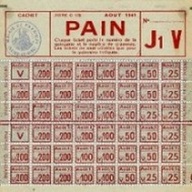

A ration card for bread

During World War II, food was rationed in France. People were issued ration tickets for bread, vegetables, meat, milk, and wine. (There were also ration tickets for non-food items such as tobacco and fabric.) Often, however, even if you had the tickets, the food items were not available on the market shelves. The German war machine was using France as its breadbasket. One of the nicknames local Parisians called the occupiers was doryphores (potato bugs) because most of France’s potatoes were shipped off to Germany. But it wasn’t only the potatoes that the Nazis requisitioned: they also took the best of French wheat, bread, butter, cream, cheese and vegetables.

If you cash to buy things at exorbitant prices on the Black Market, if you were a farmer or had friends or family who were farmers, you would be able to get your hands on decent food. Poor and working class city dwellers, and even the middle class, were left to subsist on what the Germans didn’t take. Root vegetables such as rutabagas and turnips, which had before the war been fodder for cattle, were staples. There were ersatz foods, such as jam made from what remained after grapes were pressed for wine, and instead of coffee or tea, people made do with chicory.

In the novel, the Pegorians supplement their meager war rations through ingenuity and resourcefulness. Teenaged Missak uses his slingshot to bag a duck or two in the park. Maral is dispatched by bicycle to cousins outside the city who have a backyard vegetable garden and later a chicken and egg business. The Pegorians plant tomatoes in window boxes, they barter, and eventually they risk using forged ration tickets. But during the war, they are often hungry. After another meal of bulgur and rutabagas, Maral complains that they all are suffering from “rutabaga-itis.”

Nancy Kricorian

October 9, 2012