Mushrooming

Winter is upon us, and there are far fewer mushrooms to in the woods now than there were in the late spring, summer, and autumn, but there are still fungi to find. The other day I came across a fallen oak branch that was covered in Amber Jelly Roll (Exidia Crenata), which is apparently edible, although the taste is described as bland. Today when I walked on the trails in the woods I saw lots of polypores and a few other types of mushrooms. I love the common names—Turkey Tail, False Turkey Tail, Violet-Toothed Polypore, Birch Polypore, Tinder Polypore, Artist’s Conk, Crowded Parchment, and Witch’s Butter, to name a few that I noted on my foray. I’ve started trying to learn the Latin names as well, but that is a long-term project.

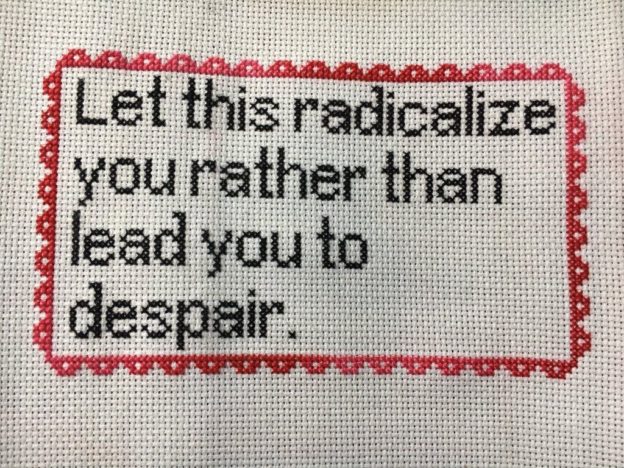

I’ve recently joined a new social media platform called Project Mushroom that was started by people who are committed to fighting for social justice and to addressing climate catastrophe. I am hoping for a viable alternative to Twitter, which is now owned by a petty and volatile right-wing billionaire. Project Mushroom is an “instance” on the Mastodon federated network, and instead of tweets the posts are called “toots,” although I hear this term is fading out because it’s a little silly and we’re just going to call them posts. What we refer to as retweets on Twitter are called boosts on Mastodon. It’s still a little lonely over there—no other Armenians, few of my organizer friends, and almost nobody I knew before I arrived. If you want an invitation to join, let me know and I’ll send you one.

It’s interesting how ubiquitous mushrooms are these days: mushrooms are to be studied, to be foraged and eaten, to be made into medicinals, to be used as metaphors for human relationships and grassroots organizing. Last year I read and loved Merlin Sheldrake’s highly entertaining Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures. After reading the book I was even more enamored of mushrooms and all their amazing properties and possibilities. I perceived the forest differently, aware of the underground mycelial networks connecting the trees, as well as the dependencies between the trees and the fungi. I thought about the way that fungi decayed organic matter to make room for new life.

I love a passage from Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark using mushrooms to think about how political change occurs. She says, “After a rain, mushrooms appear on the surface of the earth as if from nowhere. Many do so from a vast underground fungus that remains invisible and unknown. What we call mushrooms, mycologists call the fruiting body of the larger, less visible fungus. Uprisings and revolutions are often considered to be spontaneous, but less visible long-term organizing and groundwork—or underground work—often laid the foundation.”

Instead of perceiving ourselves as separate individuals, what if we understood ourselves to be created in and through our human networks? I notice in my psychotherapy sessions I often start with a report about how everyone in my life is doing—my kids, my spouse, my mother, my sister, her kids, my friends—because my well-being is entwined with theirs. I’m also reminded of one of the most inspiring slogans from Bernie Sanders’s 2020 campaign: “Are you willing to fight for that person you don’t know as much as you’re willing to fight for yourself?” What if that kind of solidarity is not about selflessness, but is grounded in an understanding that we are all connected and if others are suffering we ourselves can’t be truly whole?

Wishing you and yours a festive and sweet holiday season.

Nancy Kricorian

December 11, 2022