On Vasily Grossman’s “An Armenian Sketchbook”

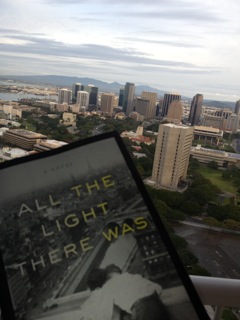

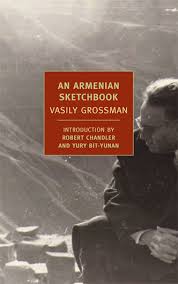

I discovered the work of Russian writer Vasily Grossman (1905-1964) a few years ago through his masterpiece, the World War II novel LIFE AND FATE. At the time, I had steeped myself in the literature of World War II because of work on my own novel, ALL THE LIGHT THERE WAS, which is set in Paris during the Nazi Occupation, and Grossman’s book was a stunning surprise. Just a few weeks ago I picked up the newly published ARMENIAN SKETCHBOOK by Grossman. It is a memoir of the two months he spent in Soviet Armenia in late 1961, soon after LIFE AND FATE was suppressed by the authorities because of its unflinching portrayal of life in Stalinist Russia. Rather than imprisoning the author, they buried his book. LIFE AND FATE, which existed as a long-hidden typescript that Grossman had left with a friend, was finally published in the late 80’s, but Grossman died without knowing that his masterwork would see the light of day.

In ARMENIAN SKETCHBOOK, Grossman manages a combination of reverence for nature and for what is best in people with irreverence for the venality of corrupt officials and the baleful influence of nationalism. There is a beautiful and deeply humane scene at the end of the book when Grossman is a guest at an Armenian peasant wedding, and an old man rises to speak in Armenian; when his words are translated, Grossman is amazed to hear him speak of the connection between the terrible suffering of the Jews in World War II and the great catastrophe the Armenians endured in 1915. For Grossman, whose mother was killed in the Nazi massacres of Jews in Berdichev in September 1941, this was a profound moment of mutual recognition. Reading his work a half century later, I was privileged to share that recognition with him.

Nancy Kricorian

This post originally appeared on Writers Read

March 23, 2013