In a used bookstore in Manhattan many years ago, I found a copy of Maria A. West’s 1875 memoir The Romance of Missions: Inside Views of Life and Labor in the Land of Ararat. Maria West was a New England missionary who had gone to the Ottoman Empire to convert the Armenians from their national church to her brand of Protestantism. On page 22 of this book, I came across a reference to an Armenian custom that I had never heard of before. West explained, “When the sons marry, they bring their wives home, and the mother-in-law generally rules them with a rod of iron. They are not allowed to speak in her presence till she grants permission, which is sometimes delayed for many years! In some cases, the mother-in-law dies before lifting the heavy yoke of imposed silence.”

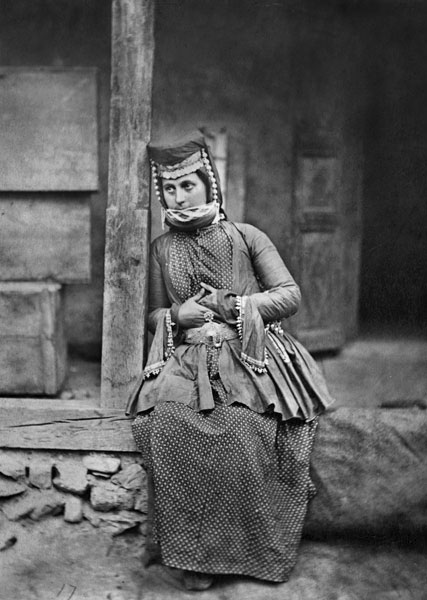

My friend Patricia Constantinian-Voskeridjian did her master’s thesis in anthropology and Armenian Studies at Columbia on the topic of this practice, known as moonch genal (to stay or to stand mute). In some families, the mother-in-law granted permission within weeks or days, and in others, the bride labored in silence for many years. In some regions, the silence was accompanied by a mouth wrap that covered the bottom half of the young woman’s face as an outward indication of her bound speech. In some villages, it was the birth of a son that would win the bride—for the daughter-in-law was called a bride for long after she was married—the right to address her in-laws.

I was fascinated by this old world practice, which had long been in disuse when my French-Canadian mother came to live in her Armenian mother-in-law’s house. But my mother told me a story about how, not long after she and my father had married, my mother had offered her mother-in-law a bit of housekeeping advice. My grandmother had replied indignantly, “What? Should the baby bird now teach the mother bird to fly?” In that response I could hear the echoes of this old country custom. Some months later, I wrote a poem in the voice of a silenced bride.

*

The Bride Has Lost Her Tongue

There sits her mother-in-law, and, according to our custom, she cannot speak in her presence.

~ The Romance of Missions, or Life and Labor in the Land of Ararat (1875)

The day I left my mother’s house

I said, “Break my bowl and

throw it in the garden. Forget

the sound of my voice.”

At night when my husband sleeps,

I whisper words I have wanted

To say during the day into the

wooden box I keep by the bed.

Under the carved roses of its lid

are insults for my mother-in-law,

the aproned witch who keeps me

in silence. When she told me

to fetch some wood, I said nothing.

I said nothing when she commanded

that I comb out her hair. Then

the words began to seep through

the house like the smell of

a dead thing behind the wall.

She says, “Shut the door,” and

I hear, “Shut it yourself, you

braying ass,” as I set the latch.

When I shake out the blankets,

insults and hair balls cloud the air.

The broom mutters my curses.

With a son, I will earn my

speech. Someday his wife

like a servant will serve me—

in sweet, melodious silence.

Nancy Kricorian

originally published in RAFT, 1996

December 28, 2012