Sanjak Camp, Bourj Hammoud, Lebanon, 7/12

My working method as a novelist has become clearer to me with each new book. Like a bird building a nest, I collect scraps and fragments of stories from people who have lived through a particular historical moment. A memory is encoded into narrative, and the narrative is anchored in a specific place and time. The historical moments that fire my imagination are, for better or worse, times of collective upheaval and violence—the Armenian Genocide, World War II, and now the Lebanese Civil War. I’m also always interested in the marginal detail, the outsider’s voice, and the version of the story that calls into question the prevailing narrative. While I love writing, I love even more the research—and the part of the research that is the most completely engaging is hearing from people their individual accounts, and then placing those personal and idiosyncratic stories within a broader historical context.

When I was in Paris researching my third novel, ALL THE LIGHT THERE WAS, which is set in the Armenian community of Belleville during the Nazi occupation, my friend Hagop served as my fixer. He arranged meetings for me with surviving Armenian members of the French Resistance, and other compatriots who had lived through the war years in Paris. But Hagop also introduced me to his circle of friends, all of them Armenians from Beirut, most of them from Bourj Hammoud, who had immigrated to France during the Lebanese Civil War.

The novel I’m working on now, about Armenians of Bourj Hammoud who immigrate to the United States during the Lebanese Civil War, was inspired by conversations I heard between Hagop and his friends while I was in Paris. They were the children and grandchildren of Genocide survivors who had reconstructed their lives and their communities in Beirut. Armenians, who benefited from the unofficial Lebanese policy of “integration without assimilation,” thrived in Beirut for several decades. The Armenian community in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s in Beirut experienced an intellectual and artistic flowering—a plethora of literary magazines, newspapers, publishing houses, theaters, plays, and folk music. Hagop and his friends were writing, directing and acting in plays; composing and singing songs; and studying painting, sculpture and architecture. And then in 1975 the Civil War erupted tearing the fabric of the Armenian community yet again. (I must say here as an aside, recent photos from the precincts of Aleppo are devastating in the way that they reproduce images from the Lebanese Civil War.)

So I see Bourj Hammoud as one of a long series of places that are not just simply locations, but are also markers of dispossession and exile. For Armenians since the Genocide, it’s a difficult task to preserve a place, or at the least to hold onto some of the public buildings, homes and other landmarks that make a neighborhood or even a city. But it turns out that what preserves those spaces the most, at least for this seemingly permanently wandering community, are the stories that people tell. So I think of my novels as kinds of preservation projects, allowing us to return to those places while acknowledging their evanescent quality. Perhaps by telling stories from their past we can gain the power and consensus to help preserve their present.

In the case of Beirut, when I started asking people about their memories of the Civil War, fully expecting that the narratives would date to 1975, I was startled by the number of people who wanted to tell me what happened among and between the Armenians of Beirut in 1958, as though a comprehension of that earlier conflict was necessary to an understanding of the later one, and the position of “positive neutrality” that the Armenians adopted in 1976. Even people who were too young to have witnessed the events of 1958 told stories that had been recounted to them by their parents—family members and friends who had been killed during that fratricidal few months, women who defiantly defended a church surrounded by militiamen and troops, and a grandfather who was framed and imprisoned for a murder that someone else had committed. Then there were the anecdotes from the early days of the Civil War in the mid-seventies. One man told of watching from the highway during the massacre at Karantina in 1976, and how the scenes he witnessed that day haunt him still.

Sometimes it seems as though my work is to walk among ghosts—the ghosts of old villages, the faded photographs of lost churches, and the long-ago stories of our dead handed down from generation to generation. In July 2012 my guide in Bourj Hammoud led me across the highway overpass to what was left of Sanjak Camp, the last Armenian refugee camp in Lebanon. Half the neighborhood had already been demolished and there were trash heaps in empty lots, but there were also small scenes of nostalgic beauty–on the balconies of the houses that remained there were potted plants and several homes had family altars hanging from their facades. I was witness not only to the lives of Sanjak Camp’s present inhabitants—people without running water, many without electricity—who were being pressured to leave so a new shopping mall could go up at that location, but I could also imagine amidst the narrow streets and crumbling staircases what the place had looked like soon after it was built in the late 30’s by Armenian refugees. Shouldn’t someone save what was left of Sanjak and restore the old wooden houses, making the place a living memorial to those resilient, hard-working survivors? My guide shrugged. Too much money, no interest, and too late. But maybe what we can do is to tell the stories, and in our stories these people and these buildings will be preserved.

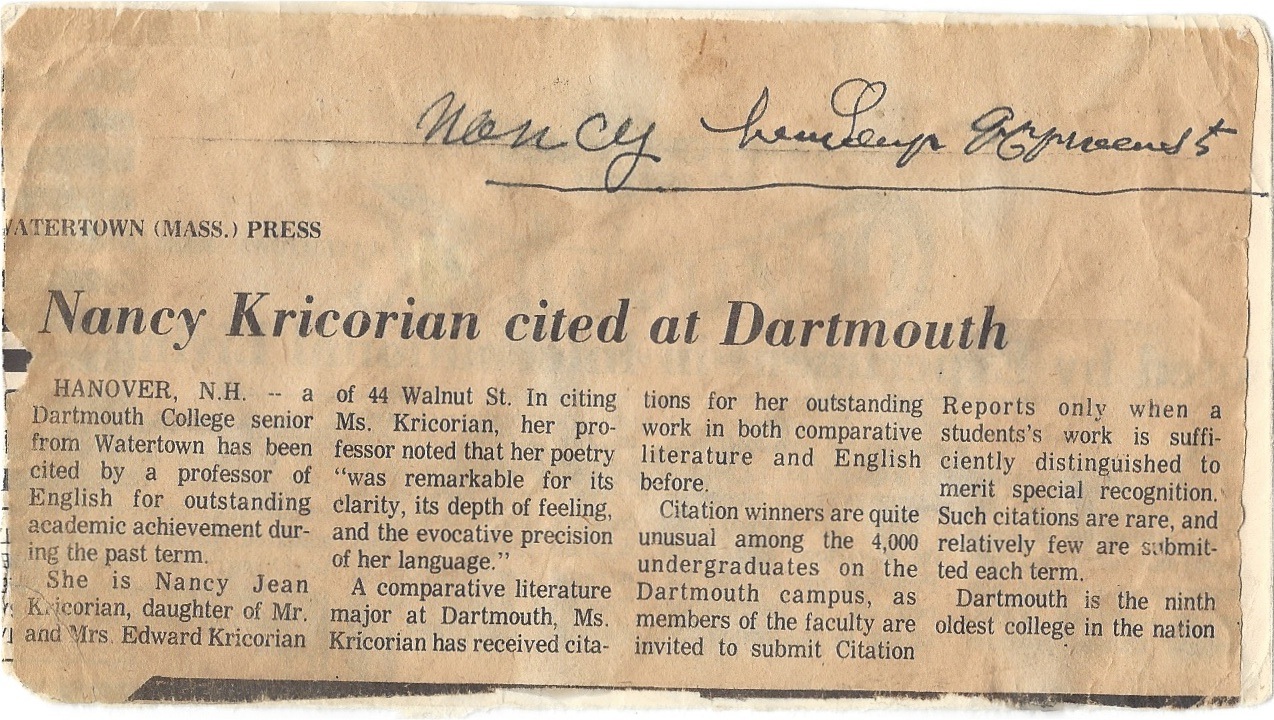

Nancy Kricorian, NYC, 11/13

A version of this piece was presented as a paper at BEIRUT NOW: A PANEL ON URBAN LANDSCAPE’S CONFLICTING DESIRES–on Nov. 7, 2013 at the CUNY Grad Center and on Nov. 12 at the American Institute of Architects.