You hear all kinds of advice about writing, and there are dozens of handbooks offering guidance, most of it is abstract and pretty useless, or else it’s so specific that it doesn’t suit. Many years ago when I was a student, a poet and teacher gave me a piece of advice that didn’t mean much at the time, but which I understood much later to be the best writing tip ever offered to me.

“Respect your process,” is what she said, and she said it before “writing process” had become a registered trademark. Her words echo in my head at moments when I am annoyed with myself for how slowly I write, or for how much time I spend researching before I even start to write, or for the fact that I don’t have the book mapped out in my head before I begin, which means that I will have to do multiple drafts to get it where it needs to be.

What I have recognized lately, however, is that process, like everything else, doesn’t stay the same. I have written three novels, and each time, the process has been different. With the first book, as I made the transition from poetry to fiction, the only way I could possibly think about taking on something as enormous as a novel was by breaking the narrative down into 10-15 page episodic chapters. I also had two small children, and was running a small business as a literary scout for foreign publishers, so the only time I could devote to writing was Friday morning. I never had writer’s block, because if I didn’t churn out those pages once a week, the novel was never going to get done.

By the time Zabelle, a fictionalized account of my grandmother’s life as an Armenian Genocide survivor and immigrant bride, was published, I was already two years into researching my second novel, Dreams of Bread and Fire, a coming-of-age story about someone of my generation growing up in the Armenian-American community. My kids were in elementary school, I had quit the scouting business, and my writing process had changed: I wrote for two hours each day. I knew other writers who could sit at a keyboard for six hours or more a day, but for me two hours was the upper limit of productive writing time. Of course, I kept tinkering with it in my head while I was sitting on the playground or even when I was sleeping, but two hours in front of the computer was my process.

When I started researching my third novel about Armenians in Paris during the Nazi occupation, I was working twenty plus hours a week for CODEPINK Women for Peace. There were many days when being at a street demonstration against the Iraq war took precedence over laboring on the novel; still I tried to stick to the two-hour a weekday regimen. But I added a new rule: even if I didn’t have two hours, I would write for twenty minutes. Twenty minutes was enough to keep the characters and the language active in my mind so that the passive work would continue. It took me ten years to write the third book, partly because of CODEPINK and the miserable state of the world, and partly because as my kids got older they took up more space in my head than they did when they were small.

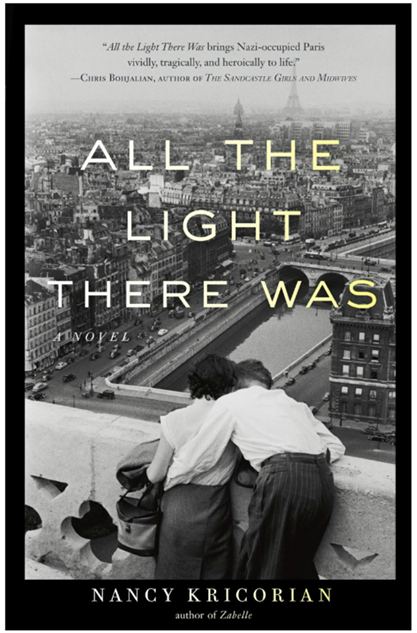

All The Light There Was, my World War II novel, was published in hardcover in 2013 and has just been reissued in paperback by She Writes Press. For two years now I’ve been researching a new novel, the fourth installment in what my editor has dubbed “The Armenian Diaspora Quartet.” It’s about Armenians in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. I haven’t started writing, and I feel anxious when I think about the fact that I don’t yet hear the sentences that will launch this story. But then I remember my mantra: “Respect your process.” I’m not entirely sure what the process will be. One of my daughters is in graduate school, and the other is a freshman in college. I’m still engaged in grassroots social justice organizing with CODEPINK, and I’ve started doing more speaking engagements, traveling, and teaching. I do know that the name of my main character is Vera, and that she grew up in the Armenian community of Bourj Hammoud before she and her family immigrated to the United States in 1980. I’m looking forward to spending a lot of time with her.

Nancy Kricorian

New York City

October 5, 2014