I’ve been meaning to send write a new blog post for weeks. On my daily to-do list for the past tens days, I have dutifully printed, “write blog,” and then ended up copying it onto the next day’s list. So here it is the end of summer—Labor Day is upon us—and I’m finally sitting down to do it.

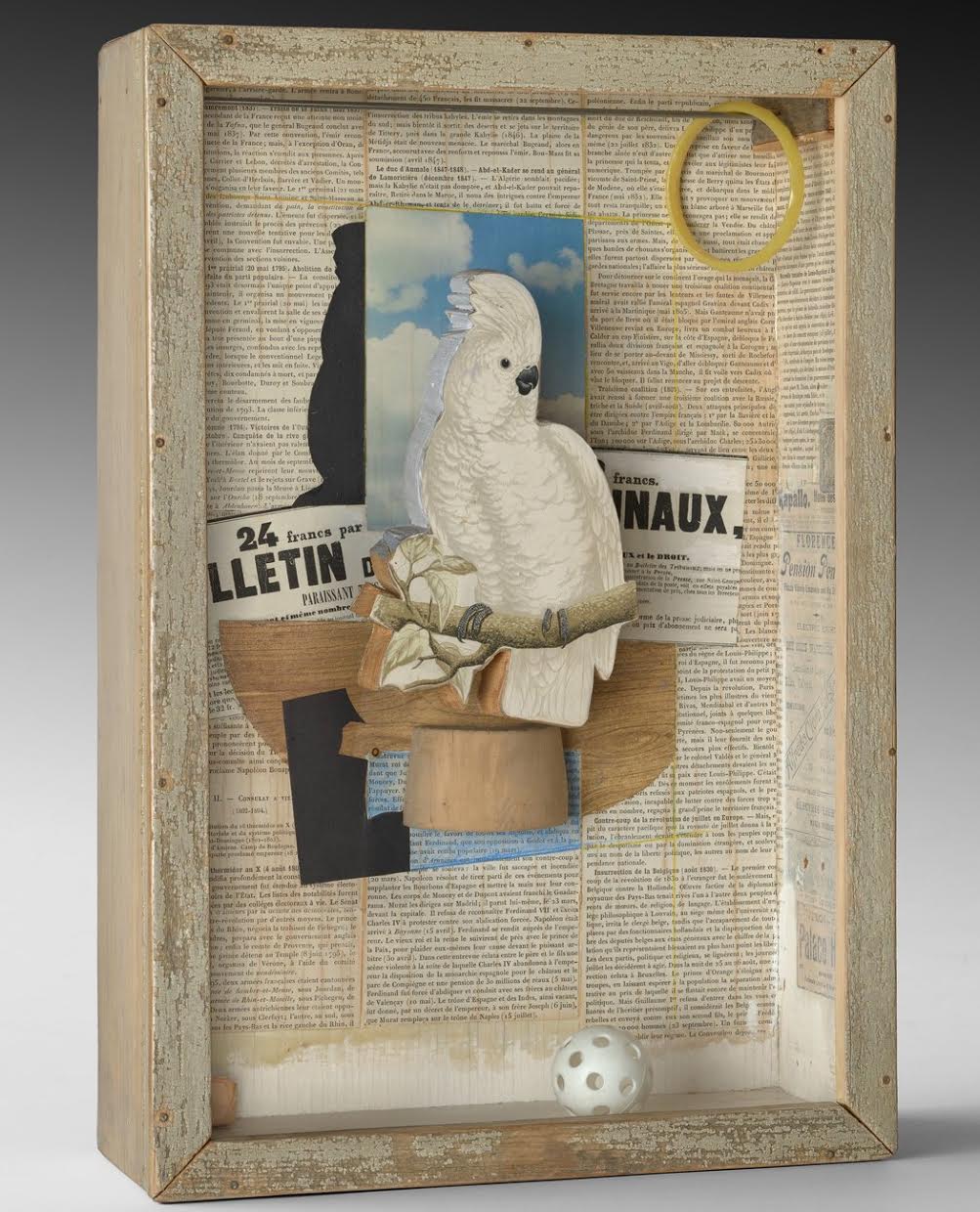

On the personal front, the summer has been a restorative one. We spent long weekends in the country where I worked in the garden and devoted at least an hour a day to watching the birds. On our front porch alone there were three active nests—a family each of robins, house wrens, and house finches with much flying to and fro by the parents and much cheeping by the nestlings. James and I also went to Chicago in July for the Socialism 2017 Conference where we heard some inspiring talks, enjoyed meals with like-minded friends, and felt comfort in assuming that we were the most conservative people in any room. We also took a family holiday to Provincetown in mid-August. I went on an Audubon-led shorebird walk, we spent afternoons on the beach, and we took in two drag shows featuring the supremely talented Jinkx Monsoon.

The work on my novel has been slow, but steady, as I continue writing while interviewing Armenians who lived the war years in Beirut in person and via Skype. The stories have been fascinating, and each anecdote feels like a piece in an enormous jigsaw puzzle I’m assembling. I’m planning another trip to Beirut for late October—will be on the ground for two weeks, staying within walking distance of the neighborhoods I’m writing about.

On the public front, each day has brought a new outrage or a new disaster, both in this country and abroad. I won’t catalogue all the misery that I’m sure you have been following as well, but I will say that I’ve been trying to find a way to process the unfathomable—both difficult to understand and seemingly bottomless—cruelty of the people currently running our national government.

While not a mental health professional, after much observation of Donald Trump’s Tweets, his public appearances, and most recently after reading the full transcript of his speech in Phoenix, I have come to the conclusion that Trump is suffering from cognitive impairment complicated by his long-term narcissistic personality disorder. (James suggested the he might also be a sociopath.) A friend shared an interview from October 2016 with singer Aimee Mann in which she talks about the song she wrote about Trump entitled, “Can’t You Tell?” (The refrain to the song is, “I don’t want this job. I can’t do this job. My God, can’t you tell, I’m unwell, I’m unwell.”) Mann said, “At this point, it’s like being angry at a rabid dog. You just have to solve the problem and get the dog in a cage.” Arguably, easier said than done. The anger is better directed at the enablers in the Republican Party who complain about Trump’s behavior and yet take no meaningful action against him because they’re still hoping to use him as a blunt instrument to push through their cruel and hateful agenda. I have some ire reserved for the Democrats who seem to have learned nothing from their defeat in November (check out this piece for a sizzling takedown of American liberals).

For things Armenian: French-Armenian entertainer Charles Aznavour received a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame at the age of ninety-three; the New Yorker published a profile of Chess Master Levon Aronian; The Telegraph (UK) ran a piece about Manchester United soccer star Henrikh Mkhitaryan; Smithsonian published an article about the “Nest Neighbors” program in Armenia to monitor white storks; Houshamadyan posted a brilliant demographic study of an Ottoman-Armenian village; Al Jazeera ran an article about war photography featuring Lebanese-Armenian photojournalist Aline Manoukian; and Print Magazine had a delightful post about Armenian typography.

On the literary beat, I enjoyed this profile of novelist Claire Messud, My favorite part was this paragraph:

Messud frowned when asked if she ever tried to make her work more commercial. ‘‘I reckon you don’t write to please other people,’’ she said, slowly and deliberately. ‘‘That’s what your integrity is.’’ Her voice was husky; we had been talking all morning, as the dogs pattered in and out. ‘‘There are bell bottoms and miniskirts, and there are pencil skirts and stiletto heels,’’ she said. Fashions come and go in literature, too. ‘‘You can write something that’s a perfect work of art, but if it’s a pencil skirt that falls in a miniskirt moment, God help you. You just have to make your pencil skirt and be you.’’

Jeff Sparrow wrote a smart and nuanced review of The Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation, an anthology edited by Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon. Adam Schatz did a brilliant podcast interview with Wally Shawn for the London Review of Books. I was thrilled to happen across this thorough and appreciative reader review of my third novel on Goodreads.

There are so many other interesting articles I could share, but who has time to read them all? I will offer you this last engaging piece from Waging Non-Violence about clowning as a tactic of creative resistance.

The bird nests by the pond and on our porch are mostly empty now, our older daughter has moved to Bushwick (in Brooklyn), and our younger daughter has headed off for her senior year in college. The flap and noise of summer will now give way to the quieter but equally colorful days of autumn. I’m hoping to get a lot of writing done!